Isis Read online

Table of Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Acknowledgements

FOR READERS

Part One - The Window

ONE

1

2

TWO

1

2

3

THREE

1

2

3

4

5

6

FOUR

1

Part Two - The Swallow

FIVE

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

SIX

1

2

3

4

5

SEVEN

1

2

3

4

EIGHT

1

2

3

Copyright Page

For

Mindy

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

With thanks to Raul Silva, M. J. Rose, Glenn Chadbourne, Simon Lipskar, Francine LaSala, Roger Cooper, Amanda Ferber, Georgina Levitt, and all of Vanguard Press.

FOR READERS

Be sure to go to www.DouglasClegg.com for the free, private newsletter and get instant access to exclusive extras and treats, including novels, novellas, stories, screensavers, and more.

Part One

The Window

Jack, swing up, and Jack swing down

Up to the window, over the ground.

Swing over the field and the garden wall—

But watch out for Jack Hackaway if you should fall.

—Nursery rhyme, 1800s

ONE

1

“Beware a field hedged with stones,” our gardener, Old Marsh, told me in his smoky voice with its Cornish inflections, as he pointed to the land near the cliff. “See there? The hedge holds in. Will not let out. Things lurk about places like that. Unseen things.”

A house, I suppose, is a stone-hedged field.

A tomb, as well.

The place where the stone-hedges ended, as they grew round our house and the gardens, was an old cave entrance that had been turned into a mausoleum beneath the ground, carved out for centuries for the bones of my ancestors.

2

The locals called it the Tombs, although it was much more than merely a series of subterranean burial chambers. It had been carved from rock by the local miners for some early Villiers ancestor and had been used just two years before my birth, when my grandmother had died. Her coffin was sealed up in granite and plaster within the Tombs, and there were spaces for other Villiers to come. My mother made me swear that I would never allow her to be buried there. “I don’t like that place,” she told me. “It’s cold and horrible and primitive. Put me in a churchyard with a proper marker. Do you promise me?” Certain that her death was years away, I promised her whatever she asked. I coaxed a smile from her when I demanded that upon my own death, she have the rag-man cart me away to the rubbish pile.

What lay below the Tombs had once been a sacred site to the Cornish people, more than a thousand years earlier. It had been a cave, leading down the cliff-side through a series of narrow passages out to sea. It was believed to be an entrance to the Otherworld—the Isle of Apples, it was sometimes called—where a stag-god and a crescent-moon mother goddess ruled.

There had been a legend, once, of a Maiden of Sorrow, who had traveled deep in the earth to the Isle of Apples to find her lover who had died a terrible death in a distant battle. When she had returned, she brought him with her and held his hand as they emerged from the winding caves into the sunlight. But when others saw the couple, they cried out in terror—for her lover’s eyes were black as pitch, and he had no mouth upon his face, just a seal of flesh as if he had not formed completely upon his journey back to the land of the living. The villagers knew he was not meant to be among them, yet the Maiden would not allow him to return to the earth. The legend went that the Maiden lived with him there at the edge of the sea, but he could not speak, nor did his eyes return to life, nor could anyone look him in the eye, lest they be driven mad from seeing the Otherworld reflected in his glance.

When someone in the nearby village was near death, the Maiden’s lover would appear at their doorway and seek entrance, as if trying to find his way back to his soul, which had remained on the other side.

There was also a large round granite stone in the field at the edge of the sunken garden, not ten paces from the Tombs. Called the Laughing Maiden, it was believed that once in early times of the Christians, another maiden went out and laughed at the priest on Sabbath day and was turned to stone there.

I went to this stone as a girl with our gardener, who believed all the old tales. Old Marsh was thought of as the local color—the crackpot old-wives-tale man of the earth who believed all the old stories and would walk backward around a graveyard to avoid upsetting the dead. He had been known to plant sheep-nettle at the stables when one of the horses had gotten sick, “to keep out bewitchments,” he’d say quite proudly. He knew a story for every stone, every fountain, every plant, and every tree at Belerion Hall. Old Marsh took it all seriously, and he warned me against upsetting spirits by changing the old gardens too much. “They like their flowers as they like them,” he said when I had been uprooting the weed-like milk thistle. “Bad luck to do that, for the saying goes, ‘Set free the thistle and hear the devil whistle.’”

At the Tombs, he gave me the most serious advice. “Never go in, miss. Never say a prayer at its door. If you are angry, do not seek revenge by the Laughing Maiden stone, or at the threshold of the Tombs. There be those who listen for oaths and vows, and them that takes it quite to heart. What may be said in innocence and ire becomes flesh and blood should it be uttered in such places.”

I looked upon the rock chamber with its small double doorways and its chains and lock, a ruins more than a mausoleum, sunken into the grassy earth with a view of the wide gray sea beyond it, and remembered such stories.

I did not intend ever to cross its threshold.

TWO

1

I was born Iris Catherine Villiers, and in the days before we came to Belerion Hall, my parents were still in love with each other. My older brothers—the “twin Villiers” as old Mrs. Haworth would later call them—Spencer and Harvard, and my eldest brother, Lewis (whom I rarely saw once we had left our first home), made up the children. To tell them apart, Spence parted his hair on the left, and Harvey, on the right. Harvey had a birthmark behind his ear, while Spence had none. Spence smelled, in the summer, distinctly of dirt and pond water, while Harvey had a fragrance as if he’d rolled in lavender.

I could tell them apart from the moment my memories began—for Harvey had always been pure warmth and gentleness whereas Spence was casually cruel and often cold, though perfectly nice in his own way. At my birth, Lewis was six, and Harvey and Spence were three. I did not have a moment in my life when one of them did not occupy my time in some way, whether for good or ill. Of the three, Harvey loved me from the moment I could remember. I loved him in the sisterly fashion for he was my protector in many ways from the rough-and-tumble of other children, and from his own twin, who resented the new baby in the family.

My earliest memories were of delight and love. We had a happy, bright, and beautiful mother who hailed from Chicago and had been, briefly, an actress and then a pianist. She had married my father, a British citizen, when they ran into each other outside of the Carthage Club in Manhattan before lunch. They fell in love over soup and roast beef at the Bellamy on Fifth Avenue, spoke of the future after cocktails at the “26,” and were marrie

d before City Hall had closed, much to the chagrin of my mother’s parents. My mother never again played the piano, and her only acting would be later, in local amateur theatricals that often thrilled me, for they seemed to be made of magic and stardust.

I was born in the summer cottage at Fisher’s Island that my American grandparents had given my parents as a wedding gift. I grew up an island girl, rarely ever going to the mainland, for I had a tutor and nanny at our house. I walked barefoot nearly all the summer, though my father called my mother “primitive” for allowing her children such immodesty.

My brothers took up slingshots when I was five. Harvey, as a joke, aimed at a bird in a tree, but when he’d shot it, he felt terrible that the bird had been hit and fell to the earth. We both ran to it, and Harvey lifted it into his hands and kissed it. He let it go and it flew off. “It was only stunned,” he said, and I told him, “Promise me never to do that again.” He promised. I made him promise a second time. We watched the bird fly off across the pink summer twilight, and then we went to bury his slingshot forever.

My brothers parted for their boarding school during the week and then returned Friday evenings to spend the weekends on the island. We played all the games of childhood, and when I was afraid to go on the swing that hung from the oak tree in our yard, Harvey had told me, “But we’re the Great Villiers Brother-and-Sister Trapeze Act!”

He would beat his chest and call out, “The greatest circus on the island! Come one, come all, to the Great Villiers Trapeze Brother-and-Sister Act!” And then he’d swing me up in his arms and rock me as if I were in a cradle. Gingerly, he would step onto the low swing, holding onto me with one hand while he squatted down upon the plank. We would swing up and down for hours, and he never once dropped me or let me go.

As we both became more comfortable with the Great Villiers Trapeze Brother-and-Sister Act, he’d swing me around and when I grew scared again, he’d say, “Close your eyes and count to ten, and when you open them, you’ll be on the ground.” And so we began to do minor acrobatics, which scared my mother half to death, for he might stand on the swing and lift me up to his shoulders while we flew out over the grass. I smelled summer lavender upon him, and sometimes I smelled the sea, too, for it was just in sight. I had no other friends on the island, and my other brothers paid no attention to me.

Harvey taught me the nursery rhymes our father had taught him when he had been my age, including the swinging rhyme about Jack Hackaway. “Jack Hackaway is a little troll who takes children to the goblins when they fall,” he said, and now and then to scare me a little he might say, as we swung, “Who goes there? Jack Hackaway, is that you?”

Sometimes I felt as if I were flying with wings on when we swung together. He always treated me as if I were the special one in the family. I loved those memories, and I cherish them even now.

By my seventh year, my father had been called to Burma by the British government, for there was a war and he was a trader in wars. So many wars came and went while I was a child that even in later years, I barely remembered what my father looked like, or how he spoke, for it was like remembering a haunting stranger seen once in a crowded train station and then never again.

My mother and my older brothers and I were packed off to my father’s ancestral home across the sea to watch over his own father, who was close to death. We moved into Belerion Hall, traveling from my beloved cottage off the Long Island Sound to the rocky cliffs of the furthest perch of Cornwall.

My first sight of the place was painful. I saw in its slate-gray curtain of rain nothing but a large prison, so unlike the delicate, wispy cottage I considered our true home, with its azalea and rhododendron bushes all around and the honeysuckle in midsummer. This new home had dead gardens that brimmed with the skeletons of briars, while moss slickened its rusty stones. Belerion Hall seemed like a millwork factory that had closed years ago, a great turgid red brick monolith to an unhappy era.

If Belerion Hall had the puritanical face of a factory, then my grandfather could best be described as the Gray Minister, which is what my brother Harvey named him immediately after our first encounter. “The Gray Minister lurks,” he’d whisper to me as I giggled. “He listens at keyholes.” Or after supper, when we played charades in the nursery, Harvey would make a signal in the air with his hands as if waving and say, “The Gray Minister comes a-tap-tapping.” This got the both of us in trouble when Spence told our grandfather of the nickname, and the elderly man came at Harvey with his gold-tipped cane, leaving my brother with bloodied trousers. Harvey had protected me, pushing me behind one of the many curtained alcoves of the corridors so that I might not be found for punishment.

Our grandfather was a tall, gaunt man of seventy, with a white wisp of beard like a goat, and a long pale face that rose up to meet the bits of peppery scrub hair left him upon his scalp.

He had eyes that always seemed red and smudged with sleeplessness, and his lips were thin and drawn back over an uneven row of teeth. He seemed perpetually smeared with a slight layer of coal dust, as if he’d been rooting around in the cellars. He rarely wore anything other than a gray coat, and beneath this, a stiff white shirt with a heavy white collar, both of which the maid had to press daily. His shoes and trousers were gray, as well, and he carried the Bible with him, though it was worn and its binding crackled and threatened to turn to dust each time he opened it.

“To spill thy seed,” he often warned Spence and Harvey, “is to invoke the wrath of God.”

To me, he would say (even when I was eleven or twelve), “Woman, thou art a temptation to Man. Clean thyself and thy thoughts. Scrub the unholy places of thy body, and bind thy flesh that it may be secret from our eyes.”

His mania did not limit itself to us. He waggled his finger at my mother, declaiming verse and psalm and invoking the deity as if the Lord were his personal servant. My mother had enough, and by the end of our first year at Belerion Hall, she locked her father-in-law into the North Wing of the estate. While servants might go there to care for him, we children could only see him on Christmas and on his birthday.

Still, we heard his shouts of wrath and brimstone and Babylon from the windows of the North Wing, often late into the night. The Gray Minister stood there in the smear of light from the flickering lamp at the window and cried out ungodly things upon our heads or upon the heads of the kings of the world.

“When your father returns,” my mother told me as she tucked me in one night when I had been agitated over my grandfather’s caterwauling, “we will find your grandfather a proper place. He is not himself. His memories are gone. This ceaseless rain must also prey upon him. We must pity him.” She kissed me on the forehead, and we said our prayers together as my grandfather continued crying out at the top of his lungs from the windows of the North Wing, “The Whore of Babylon rides upon the King of Hell! I have seen her! I have seen her! The Great Harlot! The Devil’s Dam!”

I loathed the place in the rainy times. My mother had a peculiar ailment that seemed part sorrow and part silence and grew worse when the weather grew rough and cold. In the winters, she took to her bed for weeks at a time, only seen by a nurse and the girl who took her supper. My mother’s headaches increased then, and she had begun getting deliveries in the afternoon from a druggist in the village whose boy dropped off two packages of tincture of laudanum, three times a week; and if the boy on the bicycle did not come, Mrs. Haworth sent Percy, our gardener’s son, into the village for a small bottle of Dr. Witherspoon’s Vita-Health Tonic, which smelled distinctly of rum.

Once or twice I slipped in to see her while she ate, and she would stare off at the ceiling and run her fingers through my hair and talk aimlessly.

“Your father is important, you know that. He must be away. He must be. But it is hard sometimes. We all miss him,” she said with a faint smell of tonic on her breath. “Your hair is pretty. It seems golden. In the summer, we can go to London. Wouldn’t that be fun? Yes, it would be. Perhaps your father will meet us

there. We can go to the theater or to the shops and have high tea, if you like. We can hire a driver. Or the train. Perhaps the train.”

I did not see her much during the stormy days, for it saddened me more than the mad cries of my grandfather at the upper windows.

2

When the sun came out—for the summers at Belerion Hall were often long and pleasant—I saw the distant stone arches out along the tidal island that seemed to float atop turquoise waves. I could sit near the cliff’s edge on a beautiful summer’s day and imagine the white sand below the cliffs to be full of pirate treasure. My first governess told me of the seven stones in the old harbor to the west called “The Tin Men”; they had once been miners and had gone so deep into the earth that they were turned to rock itself. Now they sat in the sea, having swallowed enemy ships that had attacked the port centuries before. I loved the legends and tales, and in the village, where some of the folk spoke the old language, I began to learn a bit of it slowly and loved being able to say a word or two in Cornish.

Mordred, Bastard Son

Mordred, Bastard Son Harrow: Three Novels (Nightmare House, Mischief, The Infinite)

Harrow: Three Novels (Nightmare House, Mischief, The Infinite) Afterlife

Afterlife The Abandoned - A Horror Novel (Thriller, Supernatural), #4 of Harrow (The Harrow Haunting Series)

The Abandoned - A Horror Novel (Thriller, Supernatural), #4 of Harrow (The Harrow Haunting Series) The Queen of Wolves

The Queen of Wolves Coming of Age: Three Novellas (Dark Suspense, Gothic Thriller, Supernatural Horror)

Coming of Age: Three Novellas (Dark Suspense, Gothic Thriller, Supernatural Horror) The Hour Before Dark

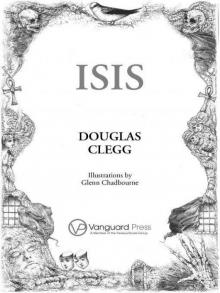

The Hour Before Dark Isis

Isis Lights Out

Lights Out The Priest of Blood

The Priest of Blood Criminally Insane: The Series (Bad Karma, Red Angel, Night Cage Omnibus) (The Criminally Insane Series)

Criminally Insane: The Series (Bad Karma, Red Angel, Night Cage Omnibus) (The Criminally Insane Series) Halloween Candy

Halloween Candy Nights Towns: Three Novels, a Box Set

Nights Towns: Three Novels, a Box Set The Children's Hour - A Novel of Horror (Vampires, Supernatural Thriller)

The Children's Hour - A Novel of Horror (Vampires, Supernatural Thriller) Dark Rooms: Three Novels

Dark Rooms: Three Novels![[Criminally Insane 01.0] Bad Karma Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/10/criminally_insane_01_0_bad_karma_preview.jpg) [Criminally Insane 01.0] Bad Karma

[Criminally Insane 01.0] Bad Karma The Abandoned - A Horror Novel (Horror, Thriller, Supernatural) (The Harrow Haunting Series)

The Abandoned - A Horror Novel (Horror, Thriller, Supernatural) (The Harrow Haunting Series) Halloween Chillers: A Box Set of Three Books of Horror & Suspense

Halloween Chillers: A Box Set of Three Books of Horror & Suspense