- Home

- Douglas Clegg

The Queen of Wolves Page 4

The Queen of Wolves Read online

Page 4

The whorls of clouds around us seemed endless tunnels within the night sky, and I followed my guide—Pythia—as she ascended farther upward, until the red ember of the burning city and countryside below us seemed a distant hearth.

The cold, dark sea lay below us now as we left sight of land. Still, I sensed our pursuer, but now his form barely touched the stream. He had fallen back, and yet I could not help but think that he still followed.

5

I began to form—in my mind’s eye—a figure of a male vampyre, but without a face and without human form. That corpse-reflection of myself I had seen in the mirrored hall on the way to the torture device that the alchemist Artephius had devised.

It was the stream that brought this to me, and yet in it, I almost felt as if it were myself—my dead mortal body—somehow in pursuit.

As a vampyre, I knew that physically I had the beauty and vibrancy of a youth of twenty, for my hair was rich and thick, and my body sinewy and strong, a musculature built in my mortal life from war and its practice. My flesh renewed itself with each day of sleep and night spent hunting for mortal blood.

I had seen myself in that mirror—for a vampyre does reflect, yet we reflect upon ourselves alone and those who have died at our hands—and the truth of my body was there before me. I was a corpse, and yet even this was an illusion of the trickery of the silver mirrors, for I was neither of the dead nor of the living—but between these states of existence. The mirror lied; and my body lied. The truth was neither, and yet it was all I knew.

I was, as all vampyres of my line may be, a shadow of my own self. Neither in this world nor the next, the children of the Serpent and of Medhya are on the borderline, the threshold between.

In my mind’s eye, I could see my dead self—that nineteen-year-old youth, bled by the Pythoness of Alkemara, rotted—my own shadow pursuing me to remind me of what I truly was beneath the beauty of vampyric glamour.

The feeling did not pass, but as dawn threatened us at our backs, Pythia dove through a smoky cloud toward the sea, as if falling to her death. I followed behind her, and saw her goal: a place where we might sleep the night.

6

We spent our first night on a small island barely larger than the grave we dug from its dirt and rocks for our rest. Just before the sun rose above us, Pythia and I had to huddle together so that no ray of its light cut through the pile of rocks beneath which we slept. She was wonderfully icy against my flesh.

She took the stolen orb from the pouch at her neck and strapped it around her waist. I felt its small, hard roundness between us. She whispered only in my mind, If you try to steal it, I will return to Nezahual. I know that’s not what you want. Not with your child in me.

I would kill you, mortal vampyre, before you did this.

You would kill your child? For when I die, your son within me also dies. I could practically hear her smile as she drifted into deep sleep, knowing how these words would be like daggers to my heart. My bond to her had not yet loosened, and though I could not trust her, I also could not risk losing her.

When the sun sank below the horizon and twilight darkened, I opened my eyes.

She sat above me, looking down as if studying me. “You and I are so different,” she said. “Still, I feel as if you know me more than anyone has.”

“It is the breath of the Sacred Kiss,” I said sleepily. “It binds us.”

“No,” she said, her mood darkening a bit. “It is something more.”

She had already drawn off all the rocks and dirt that had covered us in the day. The night was thick with clouds and silence. I smelled rain as if at some distance.

“We could return,” she said.

“What?”

“A night’s journey to the shore. Not to Nezahual. There is a country deep to the south of Aztlanteum. Emerald jungles rise up along twisting brown rivers, where none know the paths, but many mortals live. Abandoned cities from the first age of the Great Serpent still stand, carved from cavern walls lying deep in hollowed wells. You and I would be gods there, Falconer, as our tribe was in nights long past. Our child would be born, untouched by these pains and prophecies. He would grow to be king. I would grow old, but I am not jealous. You could take other lovers.”

I sat up and grabbed her at the shoulder, wishing to shake her. “You would say anything to save your own skin.”

She tugged away from me. She flashed a sullen look like a scheming child and pushed herself up. She stood over me, as if about to say something, and then thought better of it. She walked to the edge of the rock shelf that jutted out over the sea and pointed back to where our journey had begun. “It is not so far. You can hate me there as well as here.”

“You know what I must do.”

“How do you keep a dream from becoming flesh?” Pythia asked. “Medhya is a dream all vampyres know of, yet few have known her. A phantom. The darkness of night itself, held back by the Veil. She whispers like her Myrrydanai jackals.”

“Like the Great Serpent,” I said.

She half smiled as she looked at me, watching my face as if I might betray some knowledge. “You have never seen the Serpent?”

“In visions, I have seen a statue. I have felt his power in the stream.”

“My father spoke with the Serpent, as did the Nahhashim priests, and the Myrrydanai before their souls became corrupt. He is all around us, they tell us. I don’t believe it. I was a priestess—a Pythoness—and only felt stirrings of him. To make us guardians of mortals. These are stories priests use to control us. I think the Great Serpent has been vanquished, a dream disturbed. Medhya will come into this world in flesh. It is you—and this ritual—that will bring her to flesh and blood. Do you think I will live through this? Your child? Will he be born if you do this? You cannot understand how the mortal world exists until you have watched lifetimes pass, Falconer. When you came to me, in the tower of Hedammu, I did not know you were anything other than a young soldier, ready to be bled. When I brought the Sacred Kiss to you, I saw where your journey will end.”

“I saw this, too,” I said. “On an altar stone. You wear this mask.”

She glanced back at me. “I did not see the mask in my own vision. I saw you, looking at me. I saw a curved blade in your hand, like no other—it was jeweled and made of a burning gold. All around us, I felt her. Medhya. Standing near. Waiting for the Veil to tear. I heard the first whispers of the Myrrydanai priests, for the Sacred Kiss had awakened them. You—coming to Hedammu—to my towers—to my arms. This brought them.”

“You can’t be afraid of this,” I told her. “You can’t run from what you see in visions. Not everything that has been foretold will come to pass.”

She shook her head, closing her eyes. “You came to pass. I had a vision of you long before we met.”

“Why did you run from me then?”

She closed her eyes and in opening them scanned the darkening sky. “Let us not argue. We can cross a thousand miles or more if we fly swift and true.” Her wings spread from her shoulders, and I remembered how she had been terrified when she had given me the kiss that brought the breath of immortality into my lungs.

I grabbed her by the wrists. “Why did you run from me if you knew these visions?”

“Let go of me,” she snarled, shaking off my hands. “I saw your destruction. I saw my own death. A terrible shadow descended upon the earth, a terrible cry from the earth itself. I saw your doom. Mine, as well. That is where your journey takes you, Falconer—Maz-Sherah—to your Extinguishing.”

“Is this yet another game of yours?”

Her eyes lit up in anger. Her lips curved downward as she spoke. “Yes. I am playing games. A liar. Thief. Betrayer. Believe that, if you like. It will serve you well when you watch them murder your child that grows within me. When they kill me.”

More softly, I said, “There are others who suffer. I would not save my own flesh and know that I leave them to die in torment.”

“They are mortal.

They will die whether tomorrow, or in a thousand tomorrows.”

“Some are of our tribe.”

“Like the youth named Ewen who was like a ewe, tagging after you as if you were the great vampyre lord.”

“He...I could not have survived without him.”

“Yes, you love him. You with your mortal traits still intact. After more than a hundred years or so, those instincts erode.”

As I remembered Ewen, something struck me. “How could you know about him? You had fled when I brought him back to life.” In an instant, it came to me. “You...followed us?”

She moved away from me, never letting her glance leave me. “Did you think I just vanished? When the breath passes from one vampyre to another, the stream between them grows deep.”

“How long did you follow?”

“Until I saw you and your companions heading toward your capture,” she said. “I could not follow you there. But I have felt you since. I sensed you. I hid from those whispering shadows of the Myrrydanai. When the plagues came, I saw the ice of Medhya’s breath. But I knew you existed. Even in the obsidian city of Ixtar, I knew you would come to me.”

“You left us there, all those years.”

“What is a decade among my many thousands of years?” She narrowed her eyelids, as if trying to judge what to reveal and what to keep secret. “The mask called to me. You do not understand because you have not felt its call. I wished to put the seas of the Earth between us that I might never see you again. You are my destruction, Falconer. I know this.”

She ran toward the shoreline, leaping into the air, as her wings bore her aloft. I followed after—the creature that had killed me, and brought me to this existence, was my only hope—for our fates were bound together.

We soared upward. The heaviness of night drew close in a quiet mist that descended across the sea.

7

As we flew, hour by hour, I did not see anything but the dark of sky and sea and the ghost-light of the stars beyond the mist.

After many such hours, when the wind had stilled, I felt the slight warmth of a slow daybreak like a soft warning behind us, in the east, hours away, yet it bothered me to know it would come. My breath began to feel ragged. Thirst tore at my throat and dried my mouth. The pain of it had begun to grow intense, but I did not want to drink from Pythia again, for it would weaken her more than it would strengthen me.

Pythia did not fare much better. She began flying low, almost down to the waves themselves, as if expecting to dive below them should the sun reach out with its fire toward her.

The sky went from blackness to a rich purple, and we both knew the sun would burn the skies behind us within a few hours.

I saw vague shapes as if great luminous beasts lurked in the depths of the sea—serpents and tentacled creatures, behemoths and leviathans roaming the wide ocean; some I would later come to know as whales and dolphins and large schools of squid, others vanished from the Earth before mortals could observe them.

I saw what seemed to be human faces of creatures as they swam, clinging to the backs of rays and long narrow fish as they moved along the surface of the water.

As we soared farther, the sea calmed as if dead. It grew heavy and impenetrable with weed and grass at its surface.

This made me think there might be some island nearby. As we went into the fog that thickened around us, I had nearly lost hope.

The stillness of the mist, and the quiet of the water—not twenty feet below where we flew—gave me an ominous sense that we had somehow left the sea itself and had crossed the Veil.

After an hour of flying through this, I began to feel the hackles of panic along my wingspan. Within the stream, I felt Pythia’s movements draw me from the moonless sky, to a great ship with its sails slack, a prisoner within this silent calm sea.

Here was our island for the morning.

We would have extinguished in the sunlight above the great sea to the west of Aztlanteum had Pythia not seen the ship, still in the middle of the sea, as if docked.

With less than an hour to sunrise, we dived down as if falling toward the vessel.

Chapter 3

________________

THE STORM DREAMER

1

The ship had seven masts, and was longer and broader than any ship I had ever seen. In my youth, I had sailed on wide vessels off to the Holy Land for war, but these seemed like little more than planked log boats compared to this magnificent trader. Its sails were not square, but turned to the side, and hanging like rolled mats. It smelled of spice and the sea and rot. The wood of it was a deep, rich earth color and with a ruby-throated prow. The craftsmanship was of a wealthy nation—for all around it were carved wooden statues of sea gods and doglike dragons and fish and even turtles. This trading vessel looked as if it would contain the wealth of its country of origin.

At its prow, the red-painted statue of some goddess who seemed the very image of Medhya herself—for she seemed to have the aspect of a dragon, with spines along her back and arms, and what might’ve been wings in the sails that drooped along her shoulders. Her breasts were bounteous, and the smile upon her face was as fierce and dazzling as Pythia’s. The banners along the quay poles bore a cuttlefish with a warrior in armor upon its back, a spear in his fist. It was outlandish, this ship, an alien presence within the mist. As we descended I saw what might have been several masts of other such ships thrust upward in the dense atmosphere, similarly stuck in the silky waters.

During the lost century, ships often foundered on the sea as swift ice storms descended, and at other times, the wind died for many days and nights, and the sea calmed as if it were no more than an enormous lake. Days grew short, nights long. Such were the signs of the rips in the Veil, and of Medhya’s hunger to return to this Earth in flesh and blood.

Despite the size of this craft—for surely it contained many decks beneath and could have housed a village if not a small city—I did not see many men guarding its decks. Evidence of warriors lay strewn about the forecastle deck, which curved upward in a bow—armor lay heaped there, and piles of crossbows as well as shields.

Out of some hidden place, a stream of arrows shot out at us—Pythia went back up into the mist, but I was struck at the arm by one of these darts. I grabbed one of the topsail masts and clung to it. I drew the arrow out, sealing the wound quickly. I glanced down along the decks, and spied what seemed a huddle of men-at-arms, their spears and bows at the ready. They scanned the sky, but the mist covered me. To Pythia, I streamed a thought, I will deal with them, wait above until you hear my call.

Leaping the length of the mast, I landed upon the deck, among these warriors, their armor made of wood and cloth. I broke many spears, and tore the throats of men quickly that they might not surround me and hold me like dogs hold a deer until my great hunter—the sun—would arrive to slaughter me.

One after the other, the men scattered, and I lulled those who remained with spear drawn and crossbow at the ready. Yet even these I pitied, for I saw the starvation in their sunken faces as I drew off their helms and finished them quickly.

I felt the prickly heat of the sun—unseen, but known to me—and soared upward to the flat board that served as crow’s nest of the ship. I called to Pythia in the stream, and soon enough, she dropped down from the gray night.

I took her to one of the dying men, and she drank the last of him. Then, while men shouted along the ship’s edge in their terror, I led Pythia—nearly dragging her, for I feared the sun’s approach—down through the maze of corridors beneath the ship’s deck. To say I felt dread is to make light of it—for the ship had many chambers beneath it, bedrooms and bunkrooms and those that were salons for drinking and gaming—but it was the smell of death in the air that puzzled me.

As we went to the depths of the foreign ship, I saw in some of these rooms the bones and carcasses of dead men. The merchant trader had been here for more than a few nights—it must have sat in these waters too long, for I smelled n

o salted pork or wine—only those who had died. When I passed the empty storeroom I understood what had happened aboard this ship—the men had begun devouring each other.

For here, in place of meat and bread, there were men hanging from the low ceiling by great hooks, their bodies heavy with chunks of salt, and some of their limbs had been cut. How long had they been marooned here without wind, without food? How long had it taken them to turn to cannibalism?

A ship of this size might hold a thousand men, and yet I sensed fewer than twenty on board, and these moved furtively in the chambers above us. They did not wish to pass the larder in these dark hours, but remained above, on the decks, despite the threat of the flying demons that had descended and already killed several of them.

I drew Pythia into a room full of barrels—we had only outraced the sun by seconds. I rolled the heavy barrels—and did not wish to think what they might contain, but I knew they must be filled with their sustaining meat—and blocked the entrance to this dark, icy chamber.

I wrapped my arms around Pythia, and told her they would not dare follow us, though she had grown fearful with the coming sun and her vulnerability as a mortal. I kept her warm with the last of my heat until we went into the death sleep, beneath a long shelf, guarded on all sides by the great barrels of the dead.

When the night came again, we went hunting.

2

Mordred, Bastard Son

Mordred, Bastard Son Harrow: Three Novels (Nightmare House, Mischief, The Infinite)

Harrow: Three Novels (Nightmare House, Mischief, The Infinite) Afterlife

Afterlife The Abandoned - A Horror Novel (Thriller, Supernatural), #4 of Harrow (The Harrow Haunting Series)

The Abandoned - A Horror Novel (Thriller, Supernatural), #4 of Harrow (The Harrow Haunting Series) The Queen of Wolves

The Queen of Wolves Coming of Age: Three Novellas (Dark Suspense, Gothic Thriller, Supernatural Horror)

Coming of Age: Three Novellas (Dark Suspense, Gothic Thriller, Supernatural Horror) The Hour Before Dark

The Hour Before Dark Isis

Isis Lights Out

Lights Out The Priest of Blood

The Priest of Blood Criminally Insane: The Series (Bad Karma, Red Angel, Night Cage Omnibus) (The Criminally Insane Series)

Criminally Insane: The Series (Bad Karma, Red Angel, Night Cage Omnibus) (The Criminally Insane Series) Halloween Candy

Halloween Candy Nights Towns: Three Novels, a Box Set

Nights Towns: Three Novels, a Box Set The Children's Hour - A Novel of Horror (Vampires, Supernatural Thriller)

The Children's Hour - A Novel of Horror (Vampires, Supernatural Thriller) Dark Rooms: Three Novels

Dark Rooms: Three Novels![[Criminally Insane 01.0] Bad Karma Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/10/criminally_insane_01_0_bad_karma_preview.jpg) [Criminally Insane 01.0] Bad Karma

[Criminally Insane 01.0] Bad Karma The Abandoned - A Horror Novel (Horror, Thriller, Supernatural) (The Harrow Haunting Series)

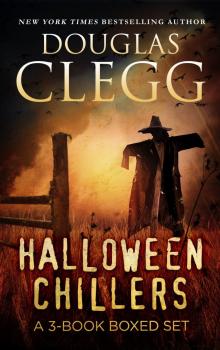

The Abandoned - A Horror Novel (Horror, Thriller, Supernatural) (The Harrow Haunting Series) Halloween Chillers: A Box Set of Three Books of Horror & Suspense

Halloween Chillers: A Box Set of Three Books of Horror & Suspense